Laws of Boolean Algebra

A

law of Boolean algebra is an

identity such as

x∨(

y∨

z) = (

x∨

y)∨

z between two Boolean terms, where a

Boolean term is defined as an expression built up from variables and the constants 0 and 1 using the operations ∧, ∨, and ¬. The concept can be extended to terms involving other Boolean operations such as ⊕, →, and ≡, but such extensions are unnecessary for the purposes to which the laws are put. Such purposes include the definition of a

Boolean algebra as any

model of the Boolean laws, and as a means for deriving new laws from old as in the derivation of

x∨(

y∧

z) =

x∨(

z∧

y) from

y∧

z =

z∧

y as treated in the section on

axiomatization.

Monotone laws

Boolean algebra satisfies many of the same laws as ordinary algebra when we match up ∨ with addition and ∧ with multiplication. In particular the following laws are common to both kinds of algebra:

| (Associativity of ∨) | x∨(y∨z) | = | (x∨y)∨z |

| (Associativity of ∧) | x∧(y∧z) | = | (x∧y)∧z |

| (Commutativity of ∨) | x∨y | = | y∨x |

| (Commutativity of ∧) | x∧y | = | y∧x |

| (Distributivity of ∧ over ∨) | x∧(y∨z) | = | (x∧y)∨(x∧z) |

| (Identity for ∨) | x∨0 | = | x |

| (Identity for ∧) | x∧1 | = | x |

| (Annihilator for ∧) | x∧0 | = | 0 |

Boolean algebra however obeys some additional laws, in particular the following:

| (Idempotence of ∨) | x∨x | = | x |

| (Idempotence of ∧) | x∧x | = | x |

| (Absorption 1) | x∧(x∨y) | = | x |

| (Absorption 2) | x∨(x∧y) | = | x |

| (Distributivity of ∨ over ∧) | x∨(y∧z) | = | (x∨y)∧(x∨z) |

| (Annihilator for ∨) | x∨1 | = | 1 |

A consequence of the first of these laws is 1∨1 = 1, which is false in ordinary algebra, where 1+1 = 2. Taking x = 2 in the second law shows that it is not an ordinary algebra law either, since 2×2 = 4. The remaining four laws can be falsified in ordinary algebra by taking all variables to be 1, for example in Absorption Law 1 the left hand side is 1(1+1) = 2 while the right hand side is 1, and so on.

All of the laws treated so far have been for conjunction and disjunction. These operations have the property that changing either argument either leaves the output unchanged or the output changes in the same way as the input. Equivalently, changing any variable from 0 to 1 never results in the output changing from 1 to 0. Operations with this property are said to be

monotone. Thus the axioms so far have all been for monotonic Boolean logic. Nonmonotonicity enters via complement ¬ as follows.

[3]

Nonmonotone laws[edit]

The complement operation is defined by the following two laws.

| (Complementation 1) | x∧¬x | = | 0 |

| (Complementation 2) | x∨¬x | = | 1. |

All properties of negation including the laws below follow from the above two laws alone.

[3]

In both ordinary and Boolean algebra, negation works by exchanging pairs of elements, whence in both algebras it satisfies the double negation law (also called involution law)

| (Double negation) | ¬¬x = x. |

But whereas ordinary algebra satisfies the two laws

| (−x)(−y) | = | xy |

| (−x) + (−y) | = | −(x + y), |

| (De Morgan 1) | (¬x)∧(¬y) | = | ¬(x∨y) |

| (De Morgan 2) | (¬x)∨(¬y) | = | ¬(x∧y). |

Completeness[edit]

At this point we can now claim to have defined Boolean algebra, in the sense that the laws we have listed up to now entail the rest of the subject. The laws

Complementation 1 and 2, together with the monotone laws, suffice for this purpose and can therefore be taken as one possible

complete set of laws or

axiomatization of Boolean algebra. Every law of Boolean algebra follows logically from these axioms. Furthermore Boolean algebras can then be defined as the

models of these axioms as treated in the

section thereon.

To clarify, writing down further laws of Boolean algebra cannot give rise to any new consequences of these axioms, nor can it rule out any model of them. Had we stopped listing laws too soon, there would have been Boolean laws that did not follow from those on our list, and moreover there would have been models of the listed laws that were not Boolean algebras.

This axiomatization is by no means the only one, or even necessarily the most natural given that we did not pay attention to whether some of the axioms followed from others but simply chose to stop when we noticed we had enough laws, treated further in the section on

axiomatizations. Or the intermediate notion of axiom can be sidestepped altogether by defining a Boolean law directly as any

tautology, understood as an equation that holds for all values of its variables over 0 and 1. All these definitions of Boolean algebra can be shown to be equivalent.

Boolean algebra has the interesting property that x = y can be proved from any non-tautology. This is because the substitution instance of any non-tautology obtained by instantiating its variables with constants 0 or 1 so as to witness its non-tautologyhood reduces by equational reasoning to 0 = 1. For example the non-tautologyhood of x∧y = x is witnessed by x = 1 and y = 0 and so taking this as an axiom would allow us to infer 1∧0 = 1 as a substitution instance of the axiom and hence 0 = 1. We can then show x = y by the reasoning x = x∧1 = x∧0 = 0 = 1 = y∨1 = y∨0 =y.

Duality principle[edit]

There is nothing magical about the choice of symbols for the values of Boolean algebra. We could rename 0 and 1 to say α and β, and as long as we did so consistently throughout it would still be Boolean algebra, albeit with some obvious cosmetic differences.

But suppose we rename 0 and 1 to 1 and 0 respectively. Then it would still be Boolean algebra, and moreover operating on the same values. However it would not be identical to our original Boolean algebra because now we find ∨ behaving the way ∧ used to do and vice versa. So there are still some cosmetic differences to show that we've been fiddling with the notation, despite the fact that we're still using 0s and 1s.

But if in addition to interchanging the names of the values we also interchange the names of the two binary operations, now there is no trace of what we have done. The end product is completely indistinguishable from what we started with. We might notice that the columns for x∧y and x∨y in the truth tables had changed places, but that switch is immaterial.

When values and operations can be paired up in a way that leaves everything important unchanged when all pairs are switched simultaneously, we call the members of each pair

dual to each other. Thus 0 and 1 are dual, and ∧ and ∨ are dual. The

Duality Principle, also called

De Morgan duality, asserts that Boolean algebra is unchanged when all dual pairs are interchanged.

One change we did not need to make as part of this interchange was to complement. We say that complement is a self-dual operation. The identity or do-nothing operation x (copy the input to the output) is also self-dual. A more complicated example of a self-dual operation is (x∧y) ∨ (y∧z) ∨ (z∧x). It can be shown that self-dual operations must take an odd number of arguments; thus there can be no self-dual binary operation.

The principle of duality can be explained from a

group theory perspective by fact that there are exactly four functions that are one-to-one mappings (

automorphisms) of the set of Boolean

polynomials back to itself: the identity function, the complement function, the dual function and the contradual function (complemented dual). These four functions form a

group under

function composition, isomorphic to the

Klein four-group,

acting on the set of Boolean polynomials.

or

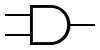

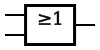

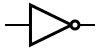

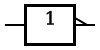

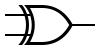

or  &

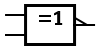

&

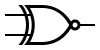

or ~

or ~

or

or

or

or

or

or